Crowd estimates are tricky and often politically sensitive.

While the politics of numbers will continue, it looks like the accuracy of crowd estimates is improving – thanks to a local company.

I remember flying in a helicopter above the Mall to cover the Million Man March in October of 1995. The U.S Park Service estimated 400,000 people showed up, and that set off a heated and very political debate. A follow up estimate by another group was more than 800,000, but its margin of error was +/- 20%. The Park Service stopped making public crowd estimates after that.

I won't argue the value of crowd estimates, but I do want to shed some light on how a reasonably accurate “standard” for estimating crowds is emerging. The recent Glenn Beck (“Restoring Honor”) and Jon Stewart’s (“Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear”) rallies received a lot of press.

|

| Stewart Rally - Courtesy Airphotoslive.com |

Both promised big turnouts. CBS wanted some numbers, good numbers, so it turned to a Virginia company, airphotoslive.com, headed by Curt Westergard.

I’ve known Curt for a couple of years and we talk about his work every few months. He’s done a lot of work with aerostats – tethered balloons. Everything from flying cameras to record what people can see from a 32nd floor condo – before the building is even built, to flying a balloon at the altitude of a proposed cell tower so residents can see if they will be able to see the tower. And now, crowd estimates at the National Mall.

|

| Grid graphic - Courtesy Airphotoslive.com |

Here’s my layman’s explanation of what goes into their crowd estimate. They define the mall as a long rectangular box (300 feet wide by 50,000 feet long), and divide it into grids. They then use a combination of high definition cameras flown from an aerostat, a camera in the Washington Monument and, if the timing is good, a shot from a GeoEye satellite to determine the density of people in each grid.

They also have to factor in angles because the shots are not from directly overhead. They plug the densities for different grids into a formula or two and come up with an estimate (+/- 10 percent). They sometimes add “crowd-sourced” pictures to tweak the estimate. Westergard often works with Professor Steve Doig of Arizona State University. It isn’t rocket science, but it is science, and they’re setting standards on which to build future estimates.

The high-def cameras suspended from the tethered aerostat (balloon) are in an array similar to a shower head. Three cameras toggle alternately left and right to sweep the crowd to produce a panoramic view equivalent to the work of nine stationary cameras. The array captures images at a rate of 4-1/2 frames per second.

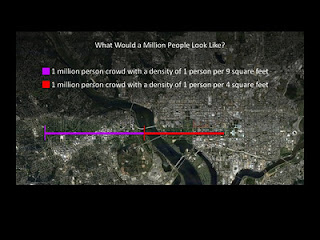

Westergard has done something that may dash the hopes of future organizers promising a million people on the Mall. Curt has “done the math” and suggests one million people will not fit on the Mall (as he defines it) – period.

|

| Airphotoslive.com graphic |

At the left is Curt's graphic showing how the Mall would have to

s-t-r-e-t-c-h into Virginia to accommodate one million people.

s-t-r-e-t-c-h into Virginia to accommodate one million people.

Even allowing only 4 square feet for each person (that’s a spot only two feet by two feet), the Mall would have to stretch across the Potomac River into Rosslyn to make room for one million people.

Crowd estimates have been political tools for years: the “anti” people had 300,000 people on the Mall; the “pro” mustered 400,000. But these new estimates are much closer to reality in terms of real numbers.

They provide a look at how many showed up, but they don’t include those who couldn’t make it, but support the cause, and they do include those who just came down to the Mall to be part of a “happening,” and have no idea of what is really going on.

Thanks to people like Curt, we are finally getting credible, scientifically-based estimates on the size of Mall crowds - facts that may finally begin to limit the bickering about “how many.” Measuring what the people in the crowds are thinking, why they’re really there, or why they aren’t there are different stories. That’s for the politicians and media pundits to tell us.

Thanks for the informative and interesting post. Not counting those that couldn't make it is an important point. For official events, such as Presidential inaugurations, the Metro system runs extra trains and may run extra buses. For other events, Metro trains run on their regular non-rush schedule. When events attract the huge number of people like we saw at the Stewart/Colbert rally, trains reach full capacity at the terminus of each line, causing people at all stations to wait until traffic at the outer stations has lessened (likely occurring after the event has begun) or causing enough frustration that people give up all together and return home.

ReplyDelete